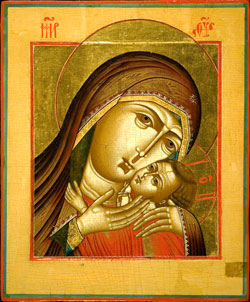

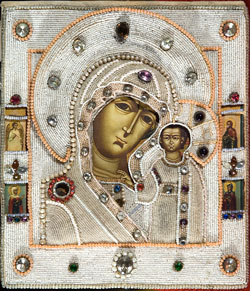

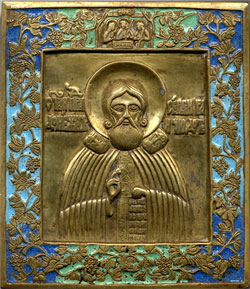

The adoption of Christianity in Russia in 988 marked the beginning of the ancient Russian art - a wonderful phenomenon in the nation’s spiritual and art life. Throughout eight hundred years (10th – 17th centuries) its evolution was accompanied by the pursuits of best expression of the images born by the Byzantine theology. The ancient Russian art sought to embody in itself the Christian faith and create “theology in color” by making the images and the words inseparable from each other. The essential element of any icon is the inscription – to avoid misinterpretation of the plot, the viewers could always read the saint’s name on the icon or other inscriptions accompanying the image.

The first piece of the Russian ancient art that has fully survived is a complex of mosaics and icon-paintings in the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev (11th century). The church décor impresses with its integrity, consistent conception and the quality of execution. Large-scale images, repeating movements of the figures and slower rhythm of the intense composition – all of this makes the painting convincingly realistic.

At the turn of the 11th and 12th centuries the priorities changed. The dominating role of the state in the icon-painting gave way to individualism of commissions from princes and the clergy. This time period is characterized by the emergence of murals in the cathedrals of the Nativity of the Virgin in the St. Anthony Monastery and St. George Cathedral in the St. George Monastery in Novgorod, and St. Michael Cathedral in St. Michael’s Golden-Domed Monastery in Kiev. It is also the time when first icons appeared, such as St. Peter and Paul in the St. Sophia Cathedral and The Annunciation in Ustyug in Novgorod. At that time the icon-painters generally came to Russia from Constantinople. Due to the fact that early icons were generally painted on the walls, the 11-century icons are commonly big in size.

The early 13th century is marked by the blossom of Russian icon-painting. It was exactly the time when historically important fresco-painting and new style murals appeared. During the Mongol invasion (1234-1480) the cultural life in Rus’ came to a standstill, yet as early as second half of the 13th century two icon-painting centers emerged in Novgorod and Rostov. The icons of that time are noted for simplified painting techniques, heavier forms and strained faces. They lack former harmony, so typical of the pre-Mongolian art period.

The first half of the 14th century marks the transfer of the metropolitan cathedra-chair from Vladimir to Moscow and the resumption of relations with Byzanthium. It was the time when Theophanes the Greek decorated in fresco the walls of the Church of the Transfiguration on Ilyin Street in Novgorod (1378). Theophanes’ painting style is extremely individual; it is distinguished for expressiveness and temperament as well as freedom and diverse painting techniques applied.

A 1405 chronicle first mentions that Theophanes the Greek, a master Prokhor and a monk Andrei Rublev painted the Annunciation Cathedral in the Moscow Kremlin. Andrei Rublev is one of the first iconographers whose name comes to mind in association with the 15th century icon-painting. The comprehension of hesychasm through the icon-painting led to searching for new stylistic decisions. The icons of The Life-giving Trinity, Christ the Redeemer, Apostle Paul, Archangel Michael, attributed to Rublev, are the essential part of the Russian cultural legacy.

At the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries the leading master of the Moscow school of icon painters was Dionisius. Together with his sons he created the iconostasis of the Cathedral of the Dormition in the Moscow Kremlin. Dionisius’ style of painting is noted for light and rhythmical character and the finest palette. In the late 16th century icon-painting schools divided into the “Godunov” and “Stroganov” art movements – the former continued a Dionisiesque tradition, while the latter sought new means of expression.

The next and the final period of icon-painting was the 17th century. The icon-painting of the “troubled times” represents the willingness to get rid of obsolete traditions and pursuits of some new genres and themes. At the same time some efforts were made in this period to traditionalize the norm. The most famous masters of that time are Nazary Istomin Savin and Simon Ushakov. With Russia’s orientation to the Western European culture during Peter I’s reign the main period of history of ancient Russian art terminated.